Photography by Taylor Chapman

Why Rushmore? Why Now?

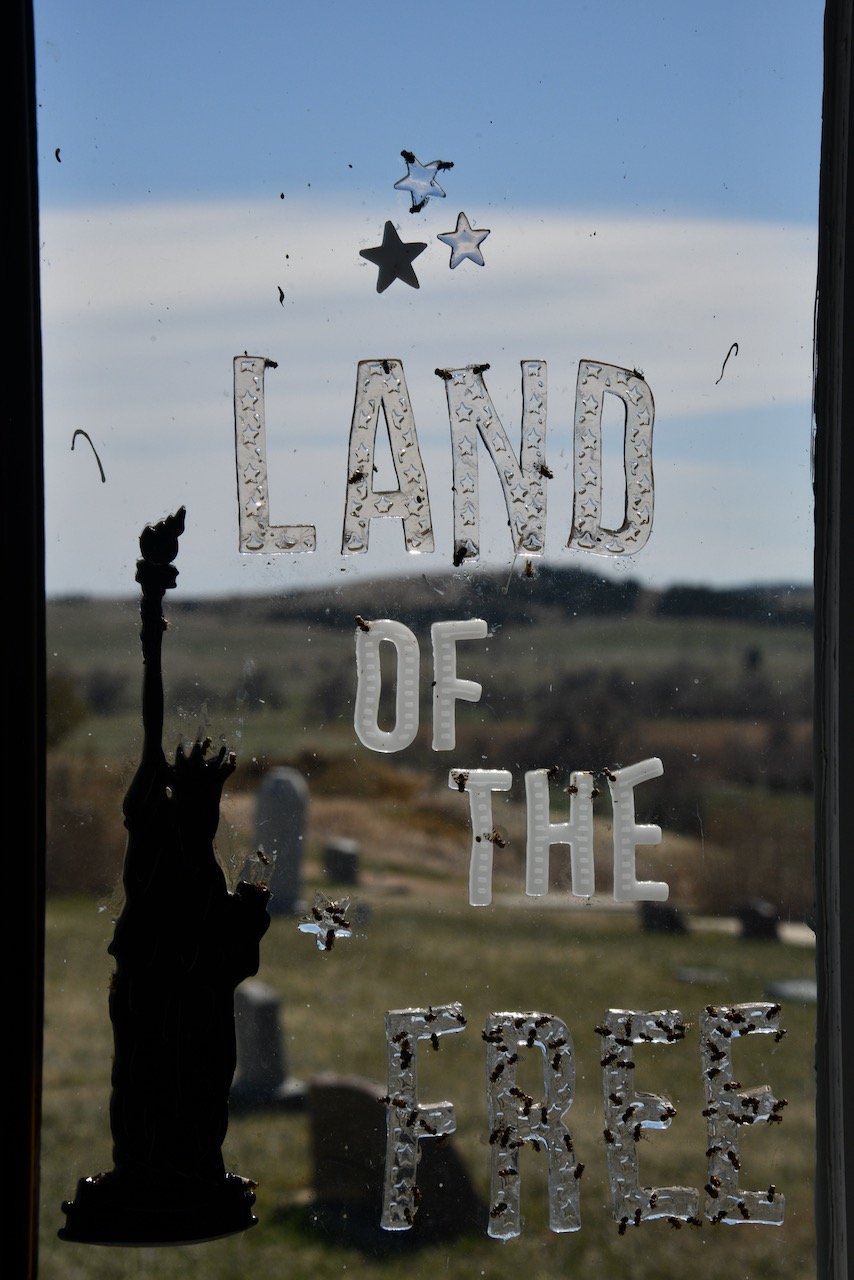

The summer of 2020 felt existential to many Americans. Not only did the pandemic challenge our notions of community, freedom, and citizenship, but the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd sparked debates over American history and how to memorialize it. Deep fissures in national identity revealed a country unable—and in some quarters unwilling—to confront the complications our national past.

It was in this context that President Trump gave a controversial speech at Mt. Rushmore on July 3, 2020, using the backdrop of the four presidents for a speech about the contours of American history and how to memorialize it. This event sparked Matt’s interest in the making, meaning, and myths of Mt. Rushmore.

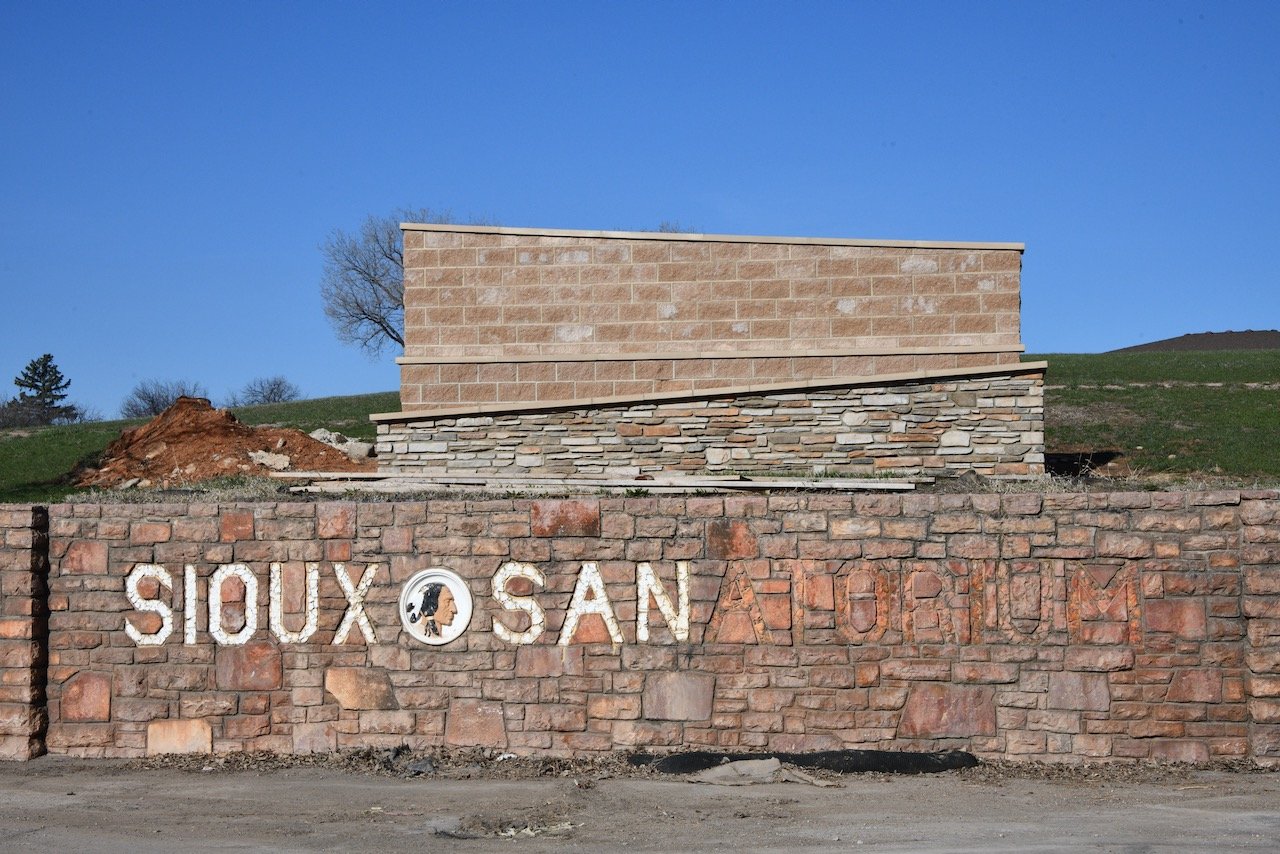

Matt engaged in some cursory research about how Rushmore’s place in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a sacred area for the Lakota and other native communities, has served as a point of pain for generations; how its sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, was a famed and accomplished artist with controversial politics and personality; how Rushmore’s construction was a mammoth publicly funded feat of engineering and endurance.

In the coming years, as Matt spent time in South Dakota and the greater Plains—in archives, in books, in the homes and offices of people who shed light on this most American of memorials—he came to think about Rushmore less as history and more of biography. The mile-high shelf of Harney Peak granite and the people who have impacted and been impacted by its evolution into the most visible piece of Americana, whose meaning has changed over generations and is disputed today, deserves to have its story told in full. This book is that attempt.

Every American generation faces unique challenges, but the American children of this pandemic era have been born into a fast-moving narrative whose current stakes are the future of our democracy. This book is an opportunity to think about what it means to be American at the quarter point of the 21st century, poised on the cusp of our 250th anniversary. To think about our past, how we represent that past in memorials and art, and to consider the United States we are developing for our children.

Emerson once wrote that “All history becomes subjective; in other words, there is properly no history; only biography.” If all history is biography, what can we learn about our country from a biography of a mountain.